There’s No “I” In Magic

For a month now — eight practices and two pre-season games — I have been the coach of a kids’ basketball team. The squad is composed of nine-, ten- and eleven-year-olds, of vastly different experience and skill.

This makes for some awkward basketball. One brief session involved explaining that you cannot walk while holding the ball. The three-second rule has exposed our school system’s inability to teach kids to count higher than two. And, no, you will never, ever make that half-court shot. How do I know? Because the ball is landing on the free-throw line — that’s how I know.

But these are impressionable young minds, and I’ve been given the rare opportunity to bend them to my will shape the outlook and attitude they’ll use for the rest of their lives. Basketball is a game, yes, but it’s also a metaphor. I’m going to put my English minor to use one way or another.

So at the first practice, the team gathered around me, I ask a question: “Who is the greatest basketball player of all time?”

“Jordan!” one kid shouts immediately.

“Wrong! Run a lap.” I’m molding minds here — it’s not a job for the timid.

“Kobe!” says another.

“Wrong! Run a lap.”

“LeBron!”

“Wrong! Run ten laps, but don’t circle around — just head off in one direction. No, don’t wait for green lights.” He trots off and I assume that he eventually made it home. Whatever.

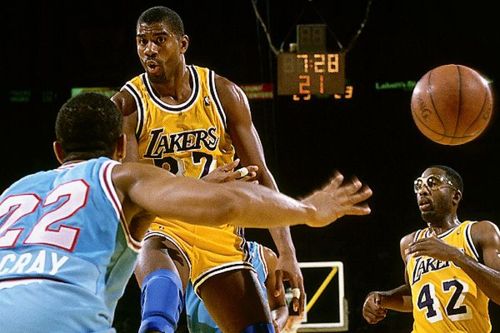

“The best basketball player of all time is Magic Johnson. This is a team sport, and he was the ultimate team player. He’s the guy they invented the triple-double for. He made everybody else on the court better. That’s what each of you is here to do.”

“Coach—”

“Run a lap! Some of you have been playing basketball for a long time, and have the advantage of entering puberty during the Bush Administration. Others have clearly confused basketball and basketweaving. Either way, we are a team. We win together or we lose together! Nobody has a good game, unless everybody has a good game! We fight and we die together! Stop crying! We shall always aspire to teamhood. Teamness. Teamosity. It was a minor; gimme a break.”

“Yes, Coach.”

“OK! Run a lap!”

But, of course, words are words and on-court glory is on-court glory and the fact that these kids — the future of basketball; the future of society — picked Jordan and Kobe and LeBron before Johnson is telling.

Later that day, on the very first play of our very first scrimmage, the biggest kid on the team — one of the most experienced — brings the ball across the line, puts his shoulder down, drives the lane and… misses. Badly.

OK, fine. Jitters. First day.

But then he does it again. And again. And again. Despite other players who were open more often than not. Despite the gentle guiding hand of his coach. Despite the innate need of human beings to gather together and distribute the risk of existence across a collective.

No passes, no looks, just a straight shot for the glory. That he kept missing was almost irrelevant.

But what can you expect, really? What gets shown on the highlight reels? What gets talked about the next day? What gets the ad contracts and the shoe deals and the unfortunate paternity suits?

You will never hear someone on ESPN say, “And here’s a solid utility player, making sure that Mr. Twenty Million Dollars actually has the ball.”

In a particularly American way, we are obsessed with the Great Man, even in the context of teams. We are drawn to stand-outs, even when their efforts don’t or can’t add up to a victory. Our fundamentally egalitarian society is at war with itself over the place of individual exceptionalism. Don’t make me go all de Tocqueville on your ass. My major was political science.

“Heroes,” some doofus once said, “rise to the occasion.” Except they don’t. They’re helped there, by teammates, by families, by society. Yes, cheering individuals is natural. They put a human face on an abstract concept like teams, or companies, or political parties. They allow us to see ourselves.

But our tendency to pack up all the glory into a nice little box and hand it entirely to one person is damaging, not only to whatever cohesiveness holds that team together, but to culture at large. Every kid who sees a strutting ball-hog feted on the tube is one step closer to trying — probable not succeeding, but trying — to be a strutting ball-hog himself. To the detriment of everybody.

Team sports are the purest sports, because they aren’t about the individual, or shouldn’t be. They’re about banding together and doing more together than you can separately. They are models for something larger. Some people are always going to stand out from the crowd they run with, but unless and until their work makes the whole better, it’s not going to add up to much. When it does, when the whole team benefits, it’s beautiful. When it doesn’t, well, that’s just one more high-profile loser.

The irony that I singled out Magic Johnson as a standard-bearer for teamwork is not lost on me. But the entire concept of a “team” needs starts somewhere. It’s not the draft or the assignments by the Rec Center and it’s certainly not SportsCenter or the maddened crowd. It’s when someone says: We can do this better together.

That kid, the big one? He’s passing now. He still palpably wants the ball, but if he doesn’t have a shot, he’ll give it to a teammate, who will then shoot and miss just as badly.

But I’m calling it progress.